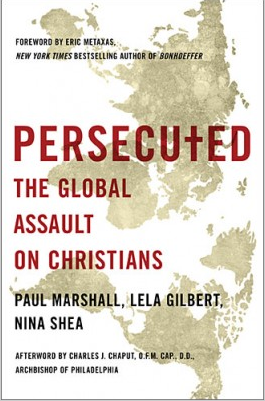

World Watch Monitor reviews Paul Marshall, Lela Gilbert & Nina Shea’s new book

This is a book designed to show that “Christians are the single most widely persecuted religious group in the world today” (p4).

With that aim, three authors well known in the field of religious advocacy give the reader the ultimate global briefing on the causes, patterns and trends in the persecution of Christians.

That the “briefing” lasts four-hundred pages is not the authors’ fault, though will perhaps condemn the book to a niche readership. But a great service has been rendered nonetheless.

That the “briefing” lasts four-hundred pages is not the authors’ fault, though will perhaps condemn the book to a niche readership. But a great service has been rendered nonetheless.

The authors don’t get bogged down in definitional discussions, but dive straight into the sinister trinity they claim to be causing the persecution of Christians around the world today – “the hunger for total political control, the desire to preserve Hindu or Buddhist privilege, and radical Islam’s urge for religious domination” (p9).

The totalitarian dynamics of the first cover the Communist and post-Communist world; Hindu and Buddhist nationalisms cover South Asia, especially India and Sri Lanka; and radical Islam is the most dispersed and global of the three forces, and half the book is dedicated to tracking its effects on the Church across every continent.

The Church in the Muslim world takes up four of the eight overview chapters and the divisions are instructive, as it is always difficult to categorise geographically the nature of the various pressures on the Church under Islam.

One chapter deals with state governments the authors claim are impeding the practice of Christianity – Malaysia, Turkey, Turkish Cyprus, Morocco, Algeria, Jordan, Yemen and the Palestinian territories are named.

This is instructive, as often the restrictions are subtle and their application to the persecution of Christians is not always obvious and perhaps all the more effective for that.

In Turkey, for example, Christians are “being smothered beneath a dense tangle of bureaucratic restrictions that thwart the ability of churches to perpetuate themselves” (p12).

A second chapter deals with the two countries the authors claim to be the worst culprits and main exporters of Islamic extremism in the world today – Saudi Arabia and Iran – and establishes that the situation is getting worse, not better, in both states and will continue to do so thanks to their petrochemical superpower status.

A third chapter looks at four states (Egypt, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Sudan) where the authors say repression is extreme and persecution comes from sources beyond the government, such as mobs and vigilantes.

A fourth chapter examines what life is like for Christians in states where the central government is not considered the main persecutor. For Iraq, Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Somalia, it is extremists in society who are often held responsible.

As a system of explanation, these four categories work quite well, though the authors would admit they inevitably overlap. The history of persecution in each country is neatly summarised alongside a round-up of latest cases and issues.

One chapter covers Communist countries (China, Vietnam, North Korea, Laos and Cuba), while another concerns post-Communist countries (Russia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and Georgia), where the dynamics of “register and control” are well outlined.

In addition to the countries where religious nationalism is a concern, such as India and Sri Lanka, one chapter looks at what really amounts to a fourth global source of persecution – national security states, such as Eritrea, Burma and Ethiopia.

The aggressive secularism seen in more Western states is not identified as a global driver, and perhaps rightly so, as the authors point out that Christians there have the ability to fight back, whereas “the persecuted do not have the ability to debate freely and seek redress and reform through democratic means” (p19).

One clear advantage of the book is its comprehensiveness. It is essentially a readable handbook.

Those looking for stories about persecuted Christians will find a few, ranging from the very well known, such as the Pakistani Christian mother, Asia Bibi, on death row in Pakistan since 2009 on blasphemy charges, to the not so well known, such as US Ambassador Joseph Ghougassian’s success in convincing the Qatari authorities to allow the building of five churches in the territory, despite their Wahabbist tendencies.

But the focus is kept firmly on the country-by-country overviews, usually in the format of stories, history, and then cases.

The authors have done their best to make each chapter readable, though the handbook format cannot be hidden, and indeed the text cries out for graphs, pictures and maps to help the reader along.

There are so many astonishing sentences about trends and situations that rush by amid the inevitably rapid pace of a global overview.

“In the 21st century, more people in China attend church services than in all Western Europe,” the author’s note (p16).

They also claim that “mosque speakers continue to pray for the death of Christians and Jews, including at Mecca’s Grand Mosque and at the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, where they serve at the pleasure of King Abdullah.” (p158).

The essential data is book-ended by an outstanding introductory chapter which gives a historical sweep of persecution, and a final chapter which upbraids the current US policy elite for a failure to speak up for the Christian persecuted.

Also highlighted is the notion that Eastern Christianity was not curtailed by the rise of Islam in the seventh century, but in the 14th, when the invading Mongols sought to ally with Christian kingdoms, drawing the ire of the Muslim rulers who responded with terrifying ferocity.

Another wave of persecution mentioned occurred in the early 20th century, when Christians in Ottoman territory were massacred, including up to one-and-a-half million Armenian Christians.

And there is the suggestion that a third wave of persecution is now underway, in the wake of the Arab Spring, as Christians flee the Palestinian areas, Lebanon, Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Egypt.

In a book this size, and with this ambition, there are some inevitable imperfections. The write-ups are sure-footed when dealing with well-known cases and government policies, but knowledge of the local or so-called “village reality” is lacking in some country overviews.

The remarkable story of the revival of the Church in North Korea is not really covered to its full extent.

Some may take issue that the increasing freedoms enjoyed by China’s house churches underneath formally restrictive legislation are underplayed and under-estimated.

Others might preserve a disappointment over definition: that, for example, pastors killed in Colombia for resisting guerrilla encroachment are not considered part of the persecuted Church.

And the final chapter may ascribe a little too much credence to the ability of US government pressure to change the fortune of the persecuted Church, rather than suggesting other forms of pressure which could perhaps be more successful.

But these are minor points in an otherwise superb overview, and the authors are well placed to warn that “the (US) Presidential bully pulpit has fallen silent regarding Middle Eastern Christians in their great hour of need” (p296-7).

This is a depressing book to read, but perhaps that is how it should be. In country after country, the facts are marshalled, laid out and laid bare, and the story is primarily a sad one; of Christians harmed, squeezed, battered and sometimes martyred.

For Christians in the Islamic-majority world, particularly, there is great despair and fear, and the reader begins to share in this. Still, there are other books that tell that story.

The authors set out to do as they promised – document one of the world’s most under-reported stories. They have provided an essential, unique, sober and sobering analysis of the persecution of Christians worldwide. It will not be a best seller, but it certainly deserves to be.

Source: World Watch Monitor

Discussion about this post